Neurotheology, explained.

When pursuing an advanced degree, make up words. That is what my colleagues and I used to tell one another in the days of theses and dissertations. The directive might strike a reader as heartily at play in this brief entry’s title. The word neurotheology rings of intellectual decadence. But it is also a word that brought The Center’s clinical staff together for a series of trainings this past summer. So bear with me.

It was Dr. Andrew Newberg, then of the University of Pennsylvania Medical School, who really launched this quirky subfield into public recognition in the early 1990s along with his colleague Dr. Eugene d’Aquili. The two were scanning brains engaged in a variety of religious activities and designated spiritual states, eventually concluding that neurogenetic tendencies towards divine transcendence were as inherent to human development as language and sex. And, fascinatingly, they managed to draw these conclusions without falling into the traps of reductionistic scientism. They could point to patterns of brain activity correlated to religion while also protecting the mysteries of spirituality and human intuition—without discrediting religion, per se. And in doing so, I add, they followed in the tradition of another trained physician, one predating them by almost a century: William James.

Widely considered the father of American psychology, William James was a behemoth of his day. The son of a preacher man—his father was an eccentric and outspoken American theologian—and the older brother to one of America’s peerless novelists, he taught the first American college course in psychology at Harvard in 1875. Twenty-five years later James was invited to give the distinguished Gifford Lectures in Scotland.[1] The addresses, putting forth psychological perspectives on spiritual experiences not easily explained by science, culminated in the now legendary The Varieties of Religious Experience: A Study in Human Nature. There is a lot to it, but here I will simply include a lengthy passage:

“There is not a single one of our states of mind, high or low, healthy or morbid, that has not some organic process as its condition. Scientific theories are organically conditioned just as much as religious emotions are; and if we only knew the faces intimately enough, we should doubtless see ‘the liver’ determining the dicta of the sturdy atheist as decisively as it does those of the Methodist under conviction anxious about his soul. When it alters in one way the blood that percolates it, we get the methodist, when in the other way, we get the atheist form of mind. So of all our raptures and our drynesses, our longings and pantings, our questions and beliefs. They are equally organically founded, be they religious or of non-religious content…

…But when other people criticize our own more exalted soul-flights by calling them ’nothing but’ expressions of our organic disposition, we feel outraged and hurt, for we know that, whatever be our organism’s peculiarities, our mental states have their substantive value as revelations of the living truth; and we wish that all this medical materialism could be made to hold it’s tongue…[but] when we think certain states of mind superior to others, is it ever because of what we know concerning their organic antecedents? NO! It is always for two entirely different reasons. It is either because we take an immediate delight in them; or else it is because we believe them to bring us good consequential fruits of life.”

William James lays the philosophical groundwork for an organic interpretation of spiritual experiences, and yet he also preserves their transcending significance. Matter, he poses, matters. It is a brilliant maneuver of integration, entangling mind and body, brain and spirit. And it solidified his place as a sturdy keystone for those neurotheologies to come.

This is why the neurtheologists (we’ll call them) set forth a hope that this unique field of study will not only enhance understandings of the human brain. They too hope it will enhance conceptions of religions and theologies. And the theologians can embrace them with open arms, because the science is diligent to avoid reductionism. In fact, theological hesitation in embracing such neuroscience is, I think, rooted in an outdated and hierarchical way of understanding the human sciences. We talk about this at The Center often; here is what I mean:

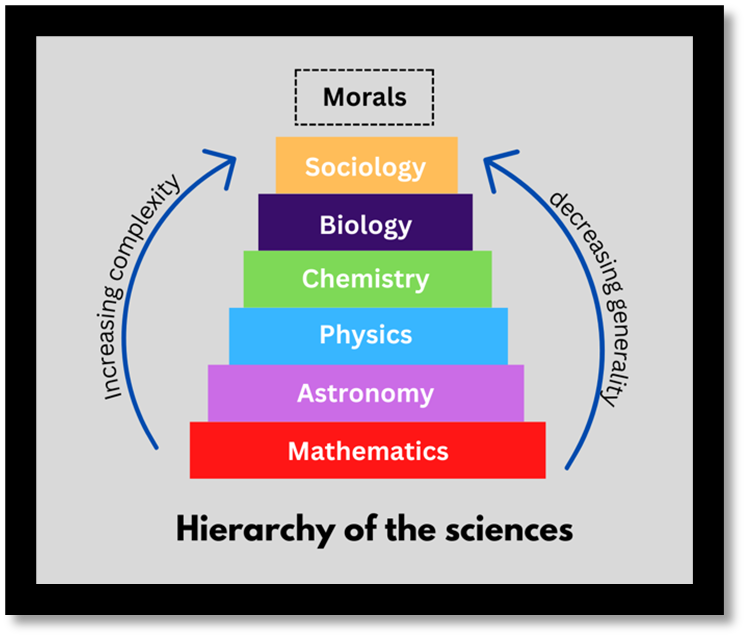

To the left you see a model of the so-called Hierarchy of the Sciences as it was first presented by the 19th century French mathematician and philosopher, Auguste Comte. He situates the different human “ologies” in an order. Those with the highest level of universality and therefore the greatest reliability (i.e., math is math no matter where you go) make up the foundations of the hierarchy. Those with the more complex network of influencing forces, the least generalizability, and the most cultural sensitivity (or perhaps, we’ll say, “subjectivity”) are up top. On this particular model, to the right, we might situate psychology right below sociology, and the theologies we might comfortably snuggle in with morals.

Now, in the last 150 years, it has at times been tempting to allow those at the bottom of the hierarchy more prestige, more validity, and more ascendancy. And so the assumption has been that there is a single direction of influence on the model, moving from the bottom up—not the other way around. If one were to change the chemistry of one’s biology, one could influence the dynamics of one’s psychology or even theology. And therefore, the bottom of the hierarchy held all the power.

But we have learned that this is not so. The direction of influence goes both directions, and one’s spiritual experiences, one’s sociological or psychological circumstances, can alter one’s biology and chemistry too. The field of neuroscience is demonstrating this all the time nowadays. And this is why the theologians need not be afraid when neurological antecedents to spiritual experiences are established by the brain people.[2] Such findings are simply evidence of the whole mind-body being working with synergy to give rise to the spiritual experience.

All of this recent scientific development really vindicates William James’s assertions and makes neurotheology a more viable and vibrant field of study. And it is all to say this: Neurotheology is the emerging field that examines the intersection of spiritual and religious experience and neuroscience, attempting to elucidate the relationships between the brain and religious experience.[3] And with all the ways that mind-body-spirit synergy makes its way to the front of recent conversations in psychology, it is as relevant a field as any. It is not just some made up word.

__________________________

[1] The Gifford Lectures in natural theology continue to this day as they have for now over 130 years. Miroslav Volf and Alexandra Walshman make upcoming lineups.

[2] What did Ebenezer Scrooge say when he encountered the spirit of his old pal, Jacob Marley? “You may be an undigested bit of beef, a blot of mustard, a crumb of cheese, a fragment of underdone potato. There’s more gravy than grave about you, whatever you are!”

[3] This definition is taken from a 2016 paper published in the Journal of Spirituality in Mental Health, written by Dixon and Wilcox.